Richard Moreland

Buried: 23.03.1891

Plot no: 11841 | Section: J07 / B

Richard Moreland was born on 16th February 1805 at Wilderness Row, Clerkenwell. The eldest son of a chimney-shaft builder called John Moreland, he was apprenticed at age 14 to a Mr. Thomas Cooper (of 149 Old Street). After a seven-year apprenticeship, he began his own millwrighting and engineering business in Teanby’s Buildings, Old Street.

Millwriting and Engineering

Moreland went into partnership with a Thomas Cooper in March 1831 (though it is unclear whether this was his former master, that man’s son, or even another person of the same name). An obituary from the Institution of Civil Engineers stated that their company ‘became celebrated for their mill gearing’, which replaced ‘old wooden lantern-wheels and pinions’. Their company also manufactured penal treadwheels for various prisons. This ancestor of the modern exercise treadmill consisted of a staircase on top of a turning iron cylinder. A punishment borne out of 19th century ideas about how labour could reform the ‘idle’ minds of convicts, prisoners had to climb the ‘everlasting staircase’. The power produced by stepping on Cooper and Moreland’s penal treadwheels was used in mustard and drug mills. The Institution of Civil Engineers obituary also tells us that the company was producing machinery used in ‘all the principal London and country breweries and distilleries’.

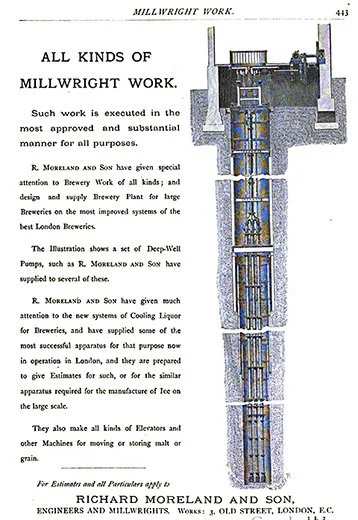

When Cooper died in 1834, Moreland bought the business with his father and uncle as sleeping partners (meaning that they provided capital but were not involved in actively managing). His brother-in-law worked with him as an office-manager and book keeper. The company later became known as Richard Moreland & Son, after the death of Moreland’s brother-in-law and the integration of his son, also Richard Moreland, into the firm in 1857. From this time until Moreland’s eventual retirement from business in 1886 (aged 81), there is evidence of the company producing machinery and materials for a wide range of purposes. Advertisements from the time show that Richard Moreland & Son offered: engineering work, general iron work, water pumps, millwrighting, brewing apparatuses, cooling liquid for breweries, ice-making machines, elevator manufacturing, hydraulic cranes, steam rollers for pressing new road surfaces, sewage pumps and fire-proof flooring.

An advert from a catalogue for engineers and contractors, 1876.

Philanthropy and the Finsbury Dispensary

At the time of his death in March 1891, Richard Moreland was undoubtedly a respected engineer and millwright. It was reported that between eighty and a hundred workmen from the company greeted his funeral procession as it arrived at the gates of Abney Park. However, the Hackney and Kingsland Gazette wrote that Moreland was better known for being ‘the mainstay of the Finsbury Dispensary for many years’. Likewise, the Islington Gazette noted that he left behind ‘a host of friends with whom he was connected in various philanthropical movements’.

Moreland is listed as a steward of the Royal General Dispensary in a May 1846 article in the Morning Advertiser. Dispensaries were sites where medical treatment and medicines were provided to the growing numbers of poor people as the urban population increased at the end of the 18th century. Another such institution was the Finsbury Dispensary, Woodbridge House, established in 1780.

By 1852, Moreland had taken a leading role in this organisation, holding the position of honorary secretary for almost the next four decades until his death. Providing free medicine to poor residents of St. Luke’s and Clerkenwell, the charity was on the brink of financial ruin when Moreland took over. By the time of his death of 1891, he ‘had lived to see the institution in a really flourishing condition’. The demand for healthcare from local residents was great; subscriptions data, published in the local press, often admitted a gap between expenditure and donations. Frequent adverts in newspapers thank donors, relay the proceedings of meetings and appeal for funds from well-of residents.

Frontispiece from the Finsbury Dispensary book by Abbotts Smith MD, 1870.

(By the late 19th century, the Finsbury Dispensary faced significant financial challenges that threatened its survival, particularly in serving the working classes of Clerkenwell and St. Luke's. In 1891, the institution's affairs reached a critical state, with insufficient funding raising fears of imminent closure and the loss of essential medical relief for the poor in the neighborhood.[12] These difficulties were temporarily averted through targeted fundraising efforts led by engineer Richard Moreland, who served as honorary secretary and mobilized subscriptions to restore operations. A unique aspect of the dispensary's approach was the provision of food rations alongside medicines when malnutrition contributed to patient conditions, helping to support recovery among the indigent by addressing both medical and nutritional needs. This practice, consistent with similar charitable institutions, underscored the holistic care model for the poor. The Finsbury Dispensary was in 1819 moved to a 'large and handsome house here' from 124 St. John Street, later moving to Woodbridge Street.)

One such appearance in the local press gives us a glimpse of Moreland’s voice, as his report to the AGM is quoted at length. He said that “the objects of the charity are to supply the sick poor with medical advice, and medicines of all kinds” and that “at the dispensary this relief is afforded to the necessitous poor, wherever they may come from”. Physicians and surgeons staffed the dispensary every weekday to offer medical support. Furthermore, the professionals even visited the homes of patients too unwell to attend the building. Across 1865, for example, Moreland announced that, “22,623 attendances were given to patients at the dispensary, and 2,253 visits were made to patients at their own homes”. There was also a Samaritan Fund available, with which medical officers could provide ‘both wine and meat, at their discretion’. Interestingly, the King of the Belgians was the patron of the charity.

The plaque near the base of the pedestal memorial for the Moreland and Andrews families.

Working life

Moreland was of a very practical turn of mind; he was ingenious in designing work and accurate and rapid in the execution of it, and was looked upon by his fellow-workmen as a leading man. He took the opportunity of attending such evening classes as were then in existence for general improvement on those things which pertained to his business. The millwrights of that period were a most intelligent and useful body of men. The greater part of his knowledge was derived from experience. Richard was equally handy at the anvil, the vice, the pattern makers’ and carpenters’ bench, and was a master in erecting work.

He was appointed by Her Majesty’s Commissioners for the Great Exhibition of 1851 one of the Local Commissioners for engineering and machinery. He was elected an Associate on March 8th, 1836.

Moreland died on the 18th of March 1891 of cystitis at the age of 86. The Islington Gazette wrote of his ‘genial and handsome presence’, calling him ‘one of the patriarchs of our parish’. They continued, ‘Everyone in Islington – worth knowing – knew Richard Moreland’. Praise was heaped onto how he conducted ‘his great life-work’, particularly with the Finsbury Dispensary, ‘an institution which has done much to alleviate the sufferings of the poor in Clerkenwell and St. Luke’s’.