Elizabeth Mounsey

Buried: 07/10/1905, aged 85

Plot no: 4659 | Section: C05 / H2

Elizabeth Mounsey was born on 8 October 1819 but not baptised until 2 September 1824, at St Leonard’s, Shoreditch on the same day as her brother Joseph, born on 5 September 1822. Her parents were Thomas and Mary Mounsey of Brunswick Place, City Road. Thomas’ trade was given as Wine Merchant.

Like her elder sister Ann Mounsey, Elizabeth showed early promise as a musician and her parents supported both sisters. Ann was responsible for much of Elizabeth’s musical training. Elizabeth played the piano and guitar in public from the age of 13. She was the pupil of German guitarist Ferdinand Pelzer and made her first performance on the guitar on 11 April 1833 at the London Tavern.

Also, like Ann, Elizabeth was an accomplished church organist. She secured a position at St Peter’s Cornhill in the City of London from 1834 until 1882, only relinquishing it in 1882 when deafness began to seriously affect her ability to function as a musician. In the 1901 Census it is noted that she had been deaf for 10 years, and she gives her profession or occupation as ‘musical professor - retired’.

The organ at St Peter’s Cornhill, City of London.

Mounsey is quoted in J. A. Hamilton's ‘Catechism of the Organ’ in 1851 speaking about the organ. “The organ at St Peter’s Cornhill was originally built in 1681 by Father Schmidt, at a cost of £210 - inclusive of painting and guilding. Upon erection of the present organ by Hill, it was found to have many wooden pipes of Schmidt’s construction which the mellowing hand of time had rendered of more than ordinary value, which still remain. It is considered one of the finest instruments in London, as many and very large additions have been made to it.”

In September 1840 Elizabeth Mounsey was in the organ loft when Felix Mendelssohn visited and tried out the instrument. Mendelssohn played two of his own works and also a J S Bach composition, Passacaglia. He asked Elizabeth to play for him but, apparently, she declined and asked for his autograph. Mendelssohn duly obliged providing his signature and the note St Peter’s Cornhill 30 Sept. 1840. Elizabeth later presented this to the parish.

The Mounsey sisters held many letters from Mendessohn, most of the original piano score of his oratorio Elijah, and the autograph score of Hear My Prayer (which had received its premier at one of Ann’s Crosby Hall Concerts in January 1845). Ann donated this to the South Kensington Museum in 1871, and gave other manuscripts to the Guildhall Library in 1880.

St Peter upon Cornhill, date unknown. Image: credit and ©bridgemanart

Elizabeth was elected to the Philharmonic Society (as was Ann). The Philharmonic Society was founded in 1813 ‘to promote the performance, in the most perfect manner possible, of the best and most approved instrumental music’ and ‘to encourage an appreciation by the public in the art of music’. It aimed to make the case for serious symphonic and chamber music. Elizabeth Mounsey also performed in the Crosby Hall concerts which Ann directed for several years, and both sisters contributed works of their own to these events.

Elizabeth wrote a great many hymn tunes, often with Elizabeth, and together they produced collections such as The Christian Month (1842), Hymns of Prayer and Praise (1868) and Sacred Harmony. A Collection of psalm and hymn tunes, chants etc…. With original interludes to each tune newly arranged for the organ or piano forte (1860).

The opening of ‘Sacrament’ the 100th hymn, from ‘Sacred Harmony’ published 1860.

Elizabeth Mouncey was listed in the London Trades’ Directory of 1856, under the category head of ‘Teachers of Music’, living at 31 Brunswick Place, City Road. The 1861 censue shows 31 Brunswick Place divided into two households: the first is headed by Mary Mounsey, widow, aged 72, an annuitant (living on the income from investments), born in Whitney (sic) Oxon. She is sharing her home with her 40-year-old daughter Elizabeth, a Professor of Music and a domestic servant, Elizabeth Banstead (23). The other household at this address consists of William Bartholomew (68), ‘fundholder’ and his wife Ann (49), a Professor of Music.

In 1891 the sisters, both retired and ‘living on own means’, where living at 58 Brunswick Place, with two general servants to support them. Elizabeth nursed and supported her sister Ann, in spite of her own increasing deafness and infirmity. She survived her sister by 14 years, and died on 3 October 1905. Bequests in her will included £550 to the Royal Society of Musicians of Great Britain and £250 each to the Society for Promoting the Due Observance of the Lord’s day and the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

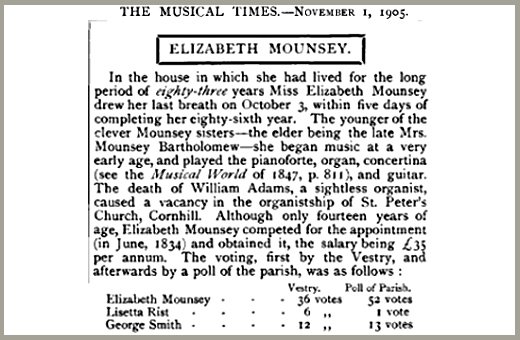

The Musical Times, in its obituary on 1 November 1905, recalled how Elizabeth, at just 14 years old, had swept the board when competing for the appointment as organist at St Peter’s. Her application had been supported by testimonials from such musical heavyweights as Samuel Wesley and James Turle, organist at Westminster Abbey. Her duties, over and above playing the organ for Sunday services, included instructing the charity school children ‘in Psalmody, on the Saturday weekly, and on other convenient or necessary occasions a may be requisite’.

Finally, The Musical Times' obituary of Elizabeth Mounsey (1 November 1905) concludes:

The death of Miss Mounsey severs an interesting link with the past. Kind-hearted, of a very retiring disposition, a true lady in her old-world courtesy, and an excellent musician, she will be remembered with affection by those who were privileged to enjoy her friendship. Her remains were quietly laid to rest in Abney Park Cemetery with that simplicity which typified her long, consistent, and useful life.

There are the silver chords

And there the ambient air,

But she who made them one with words

Makes music otherwhere.

The fallen headstone of the Mounsey family grave.

Elizabeth Mounsey is buried with her family. Her father Thomas was the first buried, in October 1849. Elizabeth’s mother, Mary and brother, Joseph Steven, are also buried here. Sadly, the headstone has suffered the damages of time and has also been displaced by a tree. The headstone has fallen forwards and to the left - it should be standing on the left side of the headstone shown in the image. If the stone was upright, it would be considerably taller than the one shown.

The above story is one example of the many stories and hidden livelihoods that can be revealed with research - regardless of the condition of the monument.