William Bithray

Buried: 10/01/1855, aged 38

Plot no: 12571 | Section: E05 / G2

William Bithray, son of Thomas and Joanna, was born in May 1816. The family lived in Britannia Row Islington. In 1831 William, ‘son of Thomas Bithray of Tabernacle Walk in the Parish of St Leonard Shoreditch, Gentm’ was apprenticed to his uncle, Stephen Bithray, whose premises were located for many years in the Royal Exchange, London. Stephen Bithray was a highly-regarded maker of scientific and engineering instruments and also a skilled glassworker. Working with Stephen, young William would have had an excellent training in the craft and business skills required to succeed. It is possible that William’s father Thomas also made lenses, or provided the basic glass to be prepared for further finishing - his work as a ‘glass drop cutter’ suggests a very specific type of glass work.

Microscope made by Bithray, Royal Exchange.

In due course William Bithray completed his apprenticeship and was admitted into the Freedom of the City in the Company of Wheelwrights in May 1839. Two years later he married Martha Greenhow, daughter of a cooper.

William and Martha soon established their family. Martha Arabella was born in 1842, followed by Sarah Rebecca (1844), their first son William (1846), then Ebenezer (1848), Thomas Richard (1850) and then another daughter, Mary Elizabeth in 1852. During this time the family occupied various addresses – Chapel Street, Clerkenwell, Charles Square, Hoxton, and Walbrook Place in Hoxton New Town.

Microscope made by Bithray, Coventry Street.

During this time William was working for the scientific instrument maker Thomas Rubergall, who had premises at 24 Coventry Street, Haymarket. Thomas Rubergall was active from 1802 until 1854 in London. He was renowned enough to have been appointed optician to George III and mathematical instrument maker and optician to the Duke of Clarence (later William IV) and to Queen Victoria. He is considered to be one of the most prominent scientific instrument retailers of the first half of the nineteenth century.

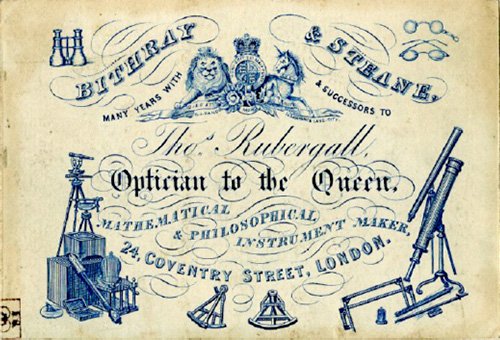

When Rubergall died in 1854, William Bithray and a fellow employee Thomas Steane succeeded to the business. Their trade card, exhibiting the continuity of the firm, is exuberantly illustrated with a selection of the instruments supplied.

The Bithray and Steane trade card, following on from Rubergall’s original design.

Tragically, William lived for only a short time after forming his partnership with Steane. He died on 3 January 1855, at 24 Coventry Street. On his death certificate his profession was given as Master Optician, his age was 38 and the cause of death was acute bronchitis. William’s sudden and unexpected death meant that a burial place had to be found quickly: he was buried on 12 January 1855 at Abney Park Cemetery, laid in a common grave with 13 others who had died between 9 and 18 January.

Another cruel blow was that William and Martha’s final child, Josiah William Bithray, was born at 24 Coventry Street, 12 days after his father’s burial. He developed bronchitis, which lingered for 3 months, before his death on 24 August. Once again, a sudden death raised the need for a burial plot, and little Josiah William was laid to rest at Abney Park on 24 August 1855. This was another burial in a common grave, with 14 others buried between 21 and 26 August.

Martha, newly-widowed, now had 6 children, ranging in age from 3 to 13 to support. There is a record in the London City Press, 17 September 1859 of 9 year old Thomas Richard Bithray’s success in the ballot for a place at the City of London Freemen’s Orphan School. Thomas was entering a school which would maintain, clothe and educate him until the age of 15. (The City of London Freemen’s Orphan School at Brixton had been established in 1850 ‘to provide for the maintenance and the religious and virtuous education of orphans of Freemen of the City of London’. It was situated on Shepherd’s Lane.)

There is a reference to Thomas in February 1865, working as an assistant to Mr John Death, a Cheapside jeweller. Thomas Richard later emigrated to the United States, became a naturalized US citizen in Illinois, married, and worked for many years as foreman in the packing department of the American Cereal company in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. He died in March 1901 and, as the Abney memorial stone records, was interred at Cedar Rapids.

The Bithray headstone.

William and Martha’s eldest son, William, died in March 1866, aged 20. He was buried at Abney Park on 6 April, in a common grave plot along with 10 others.

In later years Martha lived for a time with her daughter Martha Arabella, who had married an engraver. Martha’s son Ebenezer Bithray, an accountant’s clerk, was also in the household. The Abney Park burial register shows that Ebenezer made arrangements for his mother’s interment in a private grave in section K09. The burial took place on 29 September 1877.

The Abney record may also provide a clue to a mystery: who arranged for the imposing headstone placed on the site of Martha’s husband, William Bithray’s burial plot? This was a common grave and, although the cemetery authorities could grant permission for the erection of an inscribed stone on a common grave, the Bithray memorial stone records not just William, but also three of his sons: two of whom were buried in separate common graves (Josiah William, August 1855, in section C07 and William, 1866, in section C02. The third son, Thomas Richard, died in 1901 and is interred at Cedar Rapids, Iowa, USA, as inscribed on the stone.

The entry in the Abney Park Cemetery burial register.

There is a note written in a separate hand at the bottom of the plot entry, it reads:

Marble hd Kerb/cash in handen 10/- C no permit. The cost of a permit for erecting a head stone on a common grave was ten shillings (10/-).

These ledgers were working records, with annotations and abbreviations which are not always immediately clear to the modern reader. However, it does look remarkably like the commissioning of a marble head[stone] and kerb, for which ten shillings has been paid, cash in hand, for engraving. The C referring to a common grave for which no permit to erect a stone had previously been recorded. The record doesn’t give a date for this commission, but it would have been after the death of Thomas Richard Bithray in 1901, and most likely to have been arranged by Ebenezer, the last surviving son of William Bithray.