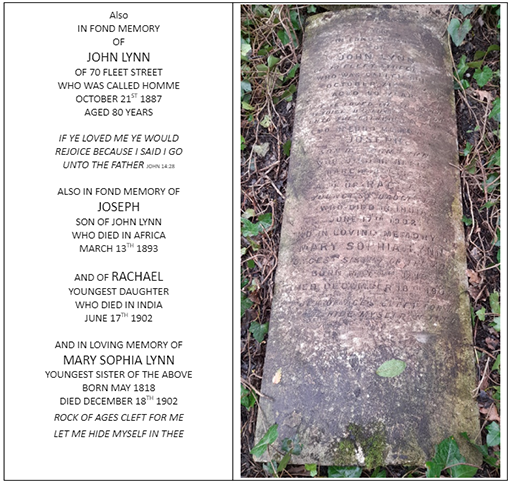

The Lynn family grave

Buried: Eight family members, various ages - from January 1850 until December 1902

Plot no: 4968 | Section: H05 / J3

John Lynn was born on 25 November 1806 and was baptised at St Bride’s Church, Fleet Street on 21 December that year. At the time of his baptism the family were living at 1 Poppin’s Court. (Poppins Court was at the end of Poppins Alley, leading from Fleet Street.) His brother, James, was born in 1809. From at least 1810 his father had a fishmonger’s business in Fleet Street.

John married Susannah Starkey at St John’s Hackney on 7 March 1832. She was the daughter of Anthony Starkey, a fishmonger from Hackney. At the time of the 1841 census John and Susannah, and John’s brother, James, his wife, Sarah and their daughter Harriet, were all living at 70 Fleet Street and both men were shellfish dealers. By 1844 John was in partnership with his father and his brother.

Susannah died in 1850 and was buried at Abney Park Cemetery on 9 January. Susannah was the 4968th burial in Abney Park, her burial took place a few months before the cemetery had been open for 10 years. The headstone has now fallen. Despite this, it is in fairly good condition.

In 1851 the two brothers were working as shellfish dealers. John was a widower, James and Sarah had another daughter, Emily, and their sister Mary, a niece, Hanna and three servants made up the household. On 26 January 1854 John married Mary Ann Starkey at St Mary, Newington. Her father Richard William Starkey was a fishmonger and the brother of John’s first wife Susannah.

At the time of the 1861 census James had left Fleet Street. John and Mary Ann were living their with two daughters, Elizabeth, 2, and Susannah, four months. Four of their children had died. John’s niece Harriet was still living in the house and there was also a cook, a housemaid and a nurse.

By the time of the next census, 1871, the family had grown, and Elizabeth and Susannah had four siblings. There were three servants in the house and John was employing 5 men (and one boy) in the fish mongering business. Mary Ann died in 1877 and was buried at Abney Park Cemetery in the grave with her four children and Susannah, on 25 February.

At the time of the 1881 census, the six children were all living in the family home. John’s occupation was listed as Refreshment House Keeper. It was known as an Oyster House and was one of the famous establishments of the Victorian era. Some were open in the evening for supper and business meetings, but Lynn’s was only open during the day.

One of the most frequently mentioned type of eating place in ‘London As it Is’ is the oyster room. Oysters were cheap fast food and could be eaten at various shellfish warehouses and in most other eateries. Oyster rooms such as Lynn’s, at 145 Fleet Street, where ‘the best accommodations are upstairs’, and Sawyer’s, St Martin’s Lane were renowned. Other famous oyster-houses of that day were Pimm's in the Poultry, and Sweeting's in Cheapside; but they were all closed at night.

The British had been fond of "Colchester Natives" since Roman times, when barrels of oysters from the remote corner of the Empire were highly prized in Rome. When the legions pulled out in 410 A. D., the oyster farms were abandoned, and oysters disappeared from British recipes until the reign of King Richard the Second.

Oysters were a popular alternative to fish, although the mixing of oysters with such meat dishes as steak-and-kidney pie (using stout and dropping the kidneys), steak, and roasted mutton occurred after the Reformation. Since beef-and-oyster pie was a classic Victorian dish, demand for the shellfish was high in nineteenth-century Britain: "as many as 80 million oysters a year being transported from Whitstable's nutrient-rich waters to London's Billingsgate Market alone."

It has been observed that "Poverty and oysters always seem to go together.” By the mid-century the native oyster beds were becoming exhausted, and the price of oysters was rising to such an extent that only the prosperous classes could afford to eat them "on the shell". Still a cheap source of protein, six oysters could still be used by the poorer Londoners as the basis for the traditional pie with a suet crust, a pound of inferior steak, onions and carrots, and a rich sauce based on a pint of porter or stout.

Fleet Street during the 1880s.

In December 1880, John Lynn was summoned for ‘keeping in his shop a well used for domestic purposes, the water of which was polluted and unfit for use’. There had been several complaints and when warned, John had agreed not to use the well and to padlock it during business hours. When the medical officer for health for the City of London visited, he found the pump in use. John said his father sank the well in 1826 but he now only used it for cleaning. John was ordered to permanently close the well.

John Lynn died suddenly on 21 October 1887 when on his way home. The Christian World explained:

“Fleet Street has lost one of its oldest, it not its very oldest inhabitant, through the death of Mr. John Lynn, the proprietor of the well-known Oyster. rooms, who died quite suddenly last Friday evening in his 82nd year. He was a member of the fraternity of Bible Christians—with whom he generally worshipped at the Hall in Beresford Street, Walworth Road—and had been to one of their conferences at Haverstock-hill, when, on his way home, he was seized with faintness in the waiting-room of the Haverstock-Hill Railway Station, and almost immediately expired. The necessary inquest was held on his remains on Tuesday, and he was buried yesterday in Abney Park. Mr. Lynn had lived Fleet-street all his life, and his face and form were very familiar to the literary and legal frequenters of that famous throughfare. His old-fashioned, but comfortable, quarters were the regular resort of many journalist and barristers. But they were no less the attraction of an altogether different class—via., the poor people of the neighbourhood, who flocked thither for the viands which Mr. Lynn's unostentatious generosity doled regularly out to them. He was held by his employees to be one of the best of masters.”

The family left London. No record of Elizabeth nor Susannah has been found. Ebenezer, Ruth, Joseph and possibly Rachael became missionaries and travelled widely overseas. Joseph’s death in Kwanjulula, Bihe, West Central Africa on 18 March 1893 was reported in the Colonies & India paper. The South London Press referred to his death in the edition printed on 2 September.

Hydrophobia appears to be causing much concern in South Africa, where it has only recently been observed, and is supposed to have been introduced from Europe by imported dogs. Amongst the victims is the Rev. Joseph Lynn, a young missionary, who only left England a few months ago. At Port Elizabeth the authorities have ordered the destruction of a large number of cats which had become by rabies.

Ebenezer married and he and his wife had a daughter when they were in India in 1900. Rachael died in India on 17 June 1900 (not 1902 as on the headstone). She was buried at Coonoor, Madres the following day. John’s sister Mary Sophia had moved to Islington and for many years was lodging in Mildmay Road. She died on 18 December 1802 and was buried in her brother’s family grave at Abney Park Cemetery.