Charles Walker Norwood

Buried: 06/06/1864, aged 64

Plot no: 6746 | Section: B05 / H3

The Norwoods

Nine members of the Norwood family are buried beneath this monument, one of only two with bee symbolism in Abney Park Cemetery (the other being a bee carved in relief on a headstone).

Charles Walker Norwood was the son of Charles and Elizabeth Norwood of Union Gardens, Shoreditch . He was born on 7th May 1801 and he married Sarah Whitbread at St Leonard’s church, on 24th June 1822.

In the years that followed, Charles and Elizabeth had at least 7 children for whom records have been found: Hannah (b.1822), Sarah Susan (b.1824), Charles (b.1827), Walker (b.1830), William (b.1833), Elizabeth (b.1835) and Edward John (b.1841). Hannah, Walker, Elizabeth and Edward were buried in the family grave at Abney.

The Norwoods lived at various addresses in the parishes of Shoreditch, Cripplegate, Holborn, Islington, and Hoxton. Charles’ occupation was given as either Paperhanger or Artist, but by 1840 he was listed in Robson’s Directory as a ‘deco.pr.hang.manfr.’ (decorative paper hanging manufacturer) living at 13 Bridport Place, New North Road. The site was near the Regent’s Canal, to the south of De Beauvoir Town, where he set up the De Beauvoir wallpaper factory.

Two Post Office directory entries (in 1844 and 1846) give the address as 13 Bridport Place, New North Road & De Beauvoir Manufactory, Rosemary Branch Bridge. From the 1851 census some family members (including Charles’ daughter Elizabeth) are living at De Beauvoir Tower, a property listed directly after Newton’s Timber Wharf, and followed by a ‘House in the Grounds of De Beauvoir Castle’, occupied by Walker Norwood and his family.

In March 1851 Charles and Sarah were not at home in Hackney but visiting William and Mary Shepherd at their home in Twickenham when the census was taken. In the 1850s Twickenham was still a rural area of Middlesex, on the western edge of London. It is possible that Charles had taken Sarah away from Hackney to enjoy the benefit of the country air, as she had been suffering from phthisis (tuberculosis) for a year or more. On 5th July 1851 Sarah Norwood succumbed to this lingering disease, and died at home. She was buried at Abney Park six days later; the first Norwood to be buried in this family plot.

Norwood Wallpaper and the Great Exhibition

In the 18th Century, wallpapers were handmade (block printed or painted) and very much only for the wealthy. This changed in the 19th Century with the growth of the middle classes who liked to display their social status through fashionable home furnishings. By the mid-19th century new printing technologies enabled this new and growing market to access a wide variety of affordable wallpapers for their homes. Britain was at the forefront of machine-printed wallpaper and Charles Norwood was one of the pioneers of the industry. His company’s designs no doubt adorned the walls of many middle class Hackney parlours.

1851 was the year of the Great Exhibition, the first international exhibition of manufactured products, housed in the vast Crystal Palace built by Joseph Paxton. This was the point in the middle of the century when Britain was being promoted as the ‘Workshop of the World’. Old craft skills were beginning to feel the pressure of competition from industrial processes which made mass-produced goods available and affordable for most people.

Charles Walker Norwood’s family business and ‘decorative paper hanging manufactory’ took part in the Great Exhibition.

The section headed Decorations for Walls, Ceilings, etc includes details of enterprises from both ends of the industrial scale – from single artist/craftsmen and women, to large concerns with factories in London and the regions. This excerpt describes the Norwood trompe l’oeil designs:

Mr Norwood of the De Beauvoir factory, Hoxton, exhibits an architectural decoration for the side of a room, composed of printed mouldings, figures, etc, on paper. The figures comprise Sir Walter Scott, Shakspere (sic) Nelson, the Queen, Prince Albert, Milton, and Robert Burns, and at a little distance have the effect of being carved in relief on oak, so well are they executed. For halls we know of no more appropriate decoration.

This was probably a one-off piece designed for the Exhibition to display the firm’s skills. The full range of the Norwoods’ patterns and techniques is not known, but it is interesting to see what the large-scale wallpaper manufacturers were producing. Another wallpaper company described in the catalogue explains the technological advances in use by the trade:

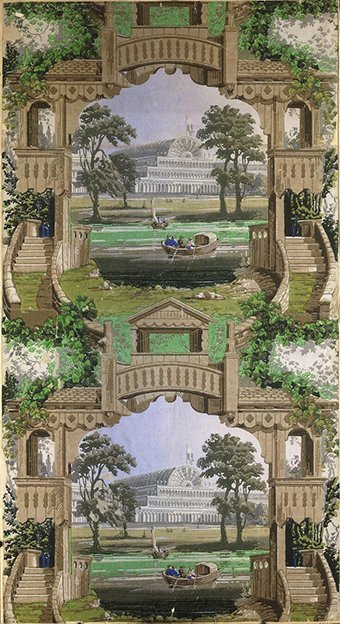

Messrs. Haywood, Higginbotham & Co, of Watling Street and Manchester, display some elegant paper hangings printed by machinery. In some of these specimens no less than sixteen colours are printed…from two cylinders, but the most remarkable and intricate of their designs is a view of the Crystal Palace, taken… in which, to combine fourteen colours in harmonious conjunction, no less than as many cylinders have been employed.

The V & A holds an example of the design, by Heywood, Higginbottom & Smith, in its wallpaper collection.

There were Exhibits from more than 50 wallpaper firms from Europe, the United States and Britain. These papers became a focus for criticism by certain designers and educators who were increasingly depressed by the decline of design standards in the industry. Richard Redgrave, at the time Inspector-General for Art, wrote an official report on the wallpapers shown at the Exhibition, in which he criticised the fact that quality was based on the number of colours used rather than any other aesthetic considerations.

Despite displaying his work at this prestigious event, on 12th June 1855, nearly four years after the Great Exhibition had closed, The London Gazette carried the declaration of Charles Walker Norwood’s bankruptcy. His property (including his ‘plant, machinery and implements of trade….. books of accounts, debts…..all securities for money …. personal estate and effects’) was taken on by official Trustees to be distributed to his creditors. After this process he was freed from debts, thus escaping imprisonment.

Second Marriage

This might not have been considered a good time to make a new marriage, but on 14th July 1855 widower Charles Walker Norwood, House Decorator, married Caroline Wheeler (30) of Lambeth. By the time of Charles’ death in 1864, the couple had produced five children: William Ambrose Charles (1855), Oswald Timothy James Walker (1858), Rose Hannah Sarah Harriett (1859) Caroline Ada (1861), and Sarah Fanny Christiana (1864).

The Norwood Children

Charles and Sarah’s daughter Hannah (33), married to paperhanger Robert Nunn, died on 30th June 1856, from phthisis (tuberculosis). She was buried at Abney Park on 6th July. Elizabeth Norwood (22) died at 13 Bridport Place on 14th March 1858. Her cause of death was recorded as epilepsy. She was buried at Abney Park on 18th March.

Infant daughter, Rose Hannah Sarah Harriet was born on 28th December 1859 at Bridport Place, and died on 12th October 1860. The cause of death was bronchitis and convulsions. She was buried at Abney Park on 19th October 1860.

By the time of the next census in April 1861 Charles Walker Norwood (59) was at home at 13 Bridport Place. A Paper Stainer employing 8 men and 4 boys, he was assisted by his son Edward (20). Living with the family was Caroline Norwood’s mother Sarah Wheeler (74) a widow, ‘formerly laundress’. Later that year, on 25 August, daughter Caroline Ada was born at Bridport Place.

Sarah Wheeler died at Bridport Place on 27th January 1862, aged 77. She was buried at Abney Park on 3rd February 1862. Later that year, on 12th September, Charles and Sarah’s son Edward John Norwood, 20 years old, journeyman paper stainer, died in the infirmary of Shoreditch workhouse. The cause of death was assessed as ‘serous apoplexy epilepsy’. The burial took place at Abney Park on 18th September.

Charles and Caroline’s daughter Sarah Fanny Christiana was born at Bridport Place on 24th February 1864. Later that year, on 30th May, her father Charles Walker Norwood died. He was 64, suffering from apoplexy and hemiplegia (a stroke). His death seems to have come suddenly and unexpectedly as he died without leaving a will. Caroline was granted administration of his estate, which amounted to ‘effects under £300’. He was buried at Abney Park on 6th June 1864. Walker Norwood (35) died on 13th September 1865, of phthisis (tuberculosis) like his mother and sister. He was buried at Abney Park five days later.

For some time after the death of her husband Caroline Norwood appears to have carried on the business. She is listed in the 1870 commercial directory as a Paperstainer at 7 Stanley Street, Hoxton, under the category heading ‘Paperhanging Manufacturers and Paperhangers’. However, by the time of the April 1881 census Caroline had moved to Walthamstow with her two daughters Caroline Ada (19) and Sarah Fanny Christiana (17), living at number 11 Queens Road. Caroline was working as a Schoolmistress, assisted by her daughters. The three women are the only occupants recorded: the school was possibly a private enterprise set up by Caroline as a means of supporting herself and her daughters.

Monument Symbolism

Since ancient times, bees - especially honey bees, have been seen to symbolise hard work and industry, to bring messages from the Divine, to set an example, to be associated with the soul, and to bring the blessing of fertility.

The Celts and Saxons believed bees were winged messengers between worlds. Ancient Egyptians thought the bee represented ka (the soul). According to Egyptian mythology, when the god Re cried, his tears turned into bees upon touching the ground, to deliver messages to mortals. In European folklore, it was believed that bees and eagles were the only members of the animal kingdom with access to heaven. The beehive is also sometimes described as being symbolic of Freemasonry (although there is no record of C W Norwood belonging to a Masonic Lodge).

With the Victorian obsession with hard work, loyalty (bees die when they sting an animal while defending their hive), team work, and industriousness, it isn't very surprising to find that bees were a favoured symbol during this time, and can be seen on monuments in other Victorian cemeteries.

There is also the practice of “telling the bees”. This may have its origins in Celtic mythology where the presence of a bee after a death signified the soul leaving the body. The tradition appears to have been most prominent in the 18th and 19th centuries in the U.S. and Western Europe.

The ritual involves notifying honey bees of a death in the family - so that the bees could share in the mourning. This generally entailed draping each hive with black crepe or some other “shred of black.” It was required that the sad news be delivered to each hive individually, by knocking once and then verbally relaying the tale of sorrow.

We can only theorise as to the reason why the beehive was the chosen symbolism for this monument. Perhaps it was as simple as a family member having a particular resonance with bees? Perhaps it was one or more of the factors mentioned above