Fungi in Abney Park Cemetery

Gina Rackley is a local naturalist and fungal specialist who has been documenting the wonderful fungi of Abney Park for over 14 years through her blog. Late last year Gina took a walk through the Park with Abney Park Trust Co-ordinator Haydn S and Trustee Martina Girvan to discuss some of the problems and potential solutions for the fungal community in the Park.

Beneficial mycorrhizal fungi Fly agaric (Amanita muscaria)

The 32 acres of Abney have been a treasure trove for fungi due to the maturity of trees which provide a large amount of living and dead wood (both standing and fallen). Diversity in fungi is supported by different age structures as trees age, die and fall. In all 296 species have been recorded in Abney Park. They form part of the tapestry of species that interlink and make the woodland a robust natural environment. They protect it from invading species of fungus that might be harmful. Gina undertook a survey late in 2021 and she, with additions by Martina and Haydn, provides thoughts on this community (past, present and future) and what needs to be done to ensure that their diversity survives.

There are many types of fungal interactions with trees. Here we will discuss beneficial mycorrhizas, potentially harmful parasites and beneficial saprophytes.

Beneficial mycorrhizal fungi

Mycorrhizal fungi and trees form a beneficial, symbiotic relationship. Symbiosis is a close, long-term relationship between two organisms. Trees produce food, in the form of glucose sugars, through photosynthesis. The trees then share this glucose with the fungus. The fungi in turn can increase the water potential of the trees through a network of mycorrhizas and deliver and share essential nutrients. They can also help trees communicate through the “wood wide web” (phrase coined by Dr. Suzanne Simard in the science journal Nature) communicating about insect attacks, drought, and other dangers.

One that used to grow like this is Fly agaric (Amanita muscaria), the traditional red capped mushroom with the white spots. It links with birch tree roots making both of them stronger. It was growing with the birch trees near the Church Street entrance, but no longer grows there.

Parasitic fungi

Parasitic fungi Giant elm bracket (Rigidoporus ulmarius) on already stressed Horse Chestnut tree

Parasitic fungi Southern bracket (Ganoderma australe)

Trees that are healthy and thriving tend not to suffer from parasitic fungi, but as they reach old age, or as they are stressed, some tree deaths are hastened by fungi that hollow out their trunks. However, hollow trees can thrive as they can flex more, and flexing better allows them to stand through strong winds in winter.

Trees decaying from the inside out provide cavities that can be hugely beneficial for a wide range of wildlife and the trees can survive for hundreds of years.

However, trees decaying from the outside in by fungal mycelium can hasten tree death. The trees’ defence against this is to shut down the section of wood that is threatened. These sections are cut off, and the amount of water and nutrients pumped up to the leaves and sugars pumped down to the roots is reduced. The tree becomes stressed and this eventually kills the tree.

One type of species in Abney that can be involved in the death of a tree is a bracket that is everywhere in Stoke Newington, Southern bracket (Ganoderma australe). It has very distinctive spores that are on most outside surfaces.

When a street tree is injured (e.g. a high sided vehicle scraping through the outer protective layer just under the top bark), the wound is then vulnerable to infection by spores. The fungus will eventually kill the tree and then grow on the dead wood until the nutrients are gone, degrading the wood as it goes.

Saprophytic (wood decaying) fungi

Pale brittlestem or Common crumble cap (Psathyrella candolleana)

Particular favourites of Gina’s are the wood decaying fungi, breaking down the wood and allowing the nutrients to be absorbed back into the living organisms that need them for growth. The most numerous in Abney have been the Inkcaps, named as they have black spores that drip as the caps self-digest, and have been used as ink when quill pens were all the rage. Abney used to be a stronghold of inkcaps with 22 species of inkcap having been recorded here.

Inkcaps are not the only wood decaying fungi. Among the many other groups that feed on dead wood are the Psathyrellas, of which 13 species have been recorded in Abney.

Yellow stainer (Agaricus xanthodermus)

Herb layer fungi

Then there are also numerous fungus species that grow in the herb layer, on the ground. The Agaricus species are large and grow at the path edges. The most common of these has been the Yellow Stainer (Agaricus xanthodermus). The yellow stainer looks like all the other Agaricus, species, more or less. Cream white cap and stem, ring round the stem. I have found 12 species of them in Abney.

Decline in fungi in Abney Park

An hour walking through Abney in the height of the fungal season should reveal a lot of species. For example, I was able to spot and identify 38 species of fungi without leaving the main paths during a walk back in October 2008. There were probably three times as many fungi present than I documented during the walk. Associated species were also obvious, invertebrates burrowing through the caps and even the teeth marks of mice on some. It was a thriving ecosystem and fungi played its part.

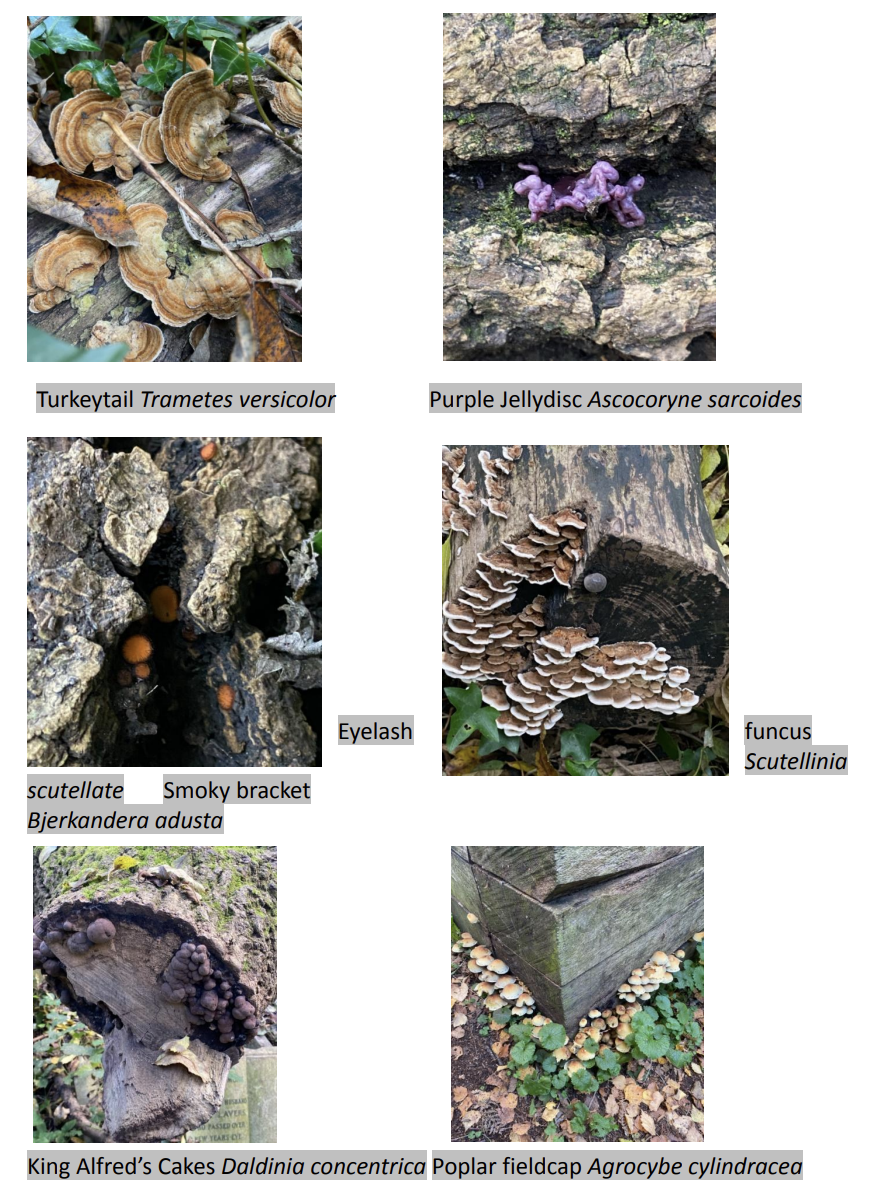

The same walk, in late October 2021, returned only 6 species of fungi. They were three long lived brackets (that live from year to year so are always present Shelf fungus, (Ganoderma adspersum), Rigidoporus adspersum and Perenniporia fraxinea) another smaller bracket, (Turkey Tail, Trametes versicolor), and two seasonal caps which I didn’t identify.

While these are incidental observations from my regular walks, I have found that fungi has been declining in Abney for the last 20 years. The number of species growing has dramatically reduced, and their numbers have also reduced.

What has changed?

Climate change: winter is not so cold, summer rain is heavier, hot spells are hotter and more frequent. Stressed trees are successfully attacked by fungus more often, reducing the structural diversity of the Park, and potentially small colonies for fungi can be eradicated.

Climate change and global trading is also exacerbating the spread of other diseases and predators. Acute oak decline is sweeping across the land too. Quoting from the Woodland Trust:

“Acute oak decline is a combination of factors which cause oak trees to become stressed. Environmental stresses like soil conditions, drought, waterlogging and pollution can all impact the tree. Insects, fungi and bacteria then move in on the vulnerable tree and push it into decline.”

Ash dieback (Hymenoscyphus fraxineus) is a fungal, originally Asian, tree disease killing ash trees over the country, but not yet in Abney.

Dutch Elm disease has been working through the elms in Abney for a long time. Elms regenerate through their roots, sending up young saplings away from the parent tree. The saplings eventually reach a size where a wood boring beetle, usually a large elm bark beetle (Scolytus scolytus), notices the tree and bores under the bark. As a carrier, the beetle brings the Dutch Elm disease fungus with it. The two fungi involved are Ophiostoma novo-ulmi and Ophiostoma ulmi.

Horse Chestnut Leaf Miner is a moth larva that burrows into the Horse Chestnut leaves eating the chlorophyll and leaving brown lines where they have been. This makes the tree leaves turn prematurely rusty brown. It won’t kill the tree, but it does stress the tree, which can leave it vulnerable to fungus attack.

Hot and dry summer spells: Climate change, combined with the urban heat island effect, creates hot and dry summer spells where the mycelium (underground root-like structures) suffer. Without them the fruiting bodies, the mushrooms etc. won’t be produced.

Heavier summer rains: There were also hugely wet spells during the summer where water flooded the ground waterlogging the soil, drowning the mycelium.

Path management: In Abney, the rain runs off some slopes onto the paths which have been compacted by footfall, clearance and repair – reducing structural diversity or temporary resurfacing. Water therefore runs off and is not retained for as long as it used to be. Water retention can help cool down the overall area and provide water for invertebrates, birds and trees to drink. The drought periods make woodchips dusty and a problem to the health of those working with them over prolonged periods, and this has resulted in discontinuing the use of wood chips for path lining. These woodchips provided a valuable food source for birds and structural age diversity for wood. They can absorb water like a sponge and stop the run off to some extent.

Woodland management: Some wood has been cleared from beside paths, resulting in the loss of fungi from hollow tree trunks.

What we can do

We can mitigate and adapt to climate change and increase the structural woodland diversity with my positive management actions.

Retaining water on site for longer: edging the paths with wood or gabions would minimise slope water run off

Where the path is wide puddles could be allowed to form in some areas potentially lined with small stones to stop them getting so muddy, and encouraging water retention.

The sides of paths could be made deeper to hold water for longer. Walking down the raised middle of the path would be unaffected, and as long as the camber to the centre of the path doesn’t hit the bottom of the vehicles used for maintenance, it would slow down the rate of water drained from this immediate area.

Larger amounts for dead wood surface area: in Tower Hamlets cemetery there is a bank held in place by tree trunk sections on their side and piled on each other, with their cut end to the path. This allows for spaces between the logs for habitat, but is deeper. Supplementing dead wood piles with fungal colonies with newer wood of the same species would sustain the colony for longer.

More sheltered wood piles: many of the dead wood piles are currently exposed to wind, rain and sunshine. To provide the optimal conditions for fungi, these could be moved into more sheltered areas.

Hope for the future

There are still many wonderful fungi to be found within the Park, and by introducing fungal specific interventions integrated into the overall management plan there is lots of potential to increase fungal diversity.

Ideally the incorporation of additional measures discussed, accompanied by regular fungal surveys, will inform future management and ensure success.